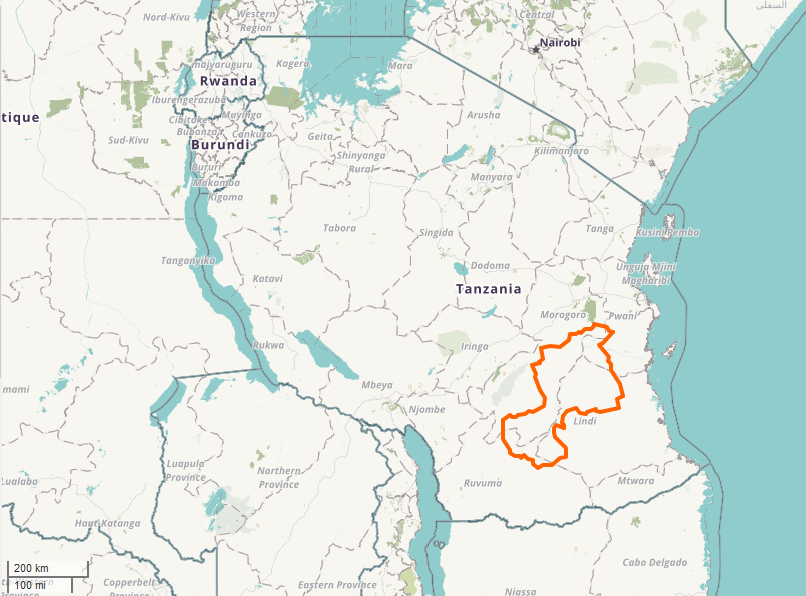

The Selous Game Reserve is one of the largest wildlife reserves in the world and in 1982 was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site due to the diversity of its wildlife and undisturbed nature. Located in the southern portion of Tanzania, it covers a total area of 50,000 km2 (the same size as Costa Rica) and is home to the mighty Rufiji River (pictured left) which flows into the Indian Ocean. Within the reserve no permanent human habitation or permanent structures are permitted and while most of the reserve is protected or remains set aside for game hunting through a number of privately leased hunting concessions, there are several camps set along the river.

A map showing the Selous Game Reserve land mass and location compared to Kenya.

Tanzania, during its long history in conservation, is home to one of Africa’s largest elephant populations and in 1989 was a strong backer of the CITES regulation that rendered the international trade in ivory illegal. In 1976, it was estimated the Selous-Mikumi ecosystem was home to over 109,000 elephants, at the time considered the largest in the world; however, recent numbers show a significant decline. In 2013, the Frankfurt Zoological Society estimated the elephant population to be around 13,000 in the Selous Game Reserve. For the first time in recent history, the Selous ecosystem, and Tanzania itself, was no longer home to one of the largest elephant populations in Africa.

A mother and baby elephant in the river bed in Selous.

According to a report published in April 2014 from c4ads and Born Free Foundation, there are several factors contributing to the decline in the elephant population in Tanzania but the biggest is poaching. A DNA analysis featured in National Geographic in 2013 showed that of 11 tons of ivory seized in raids in Taiwan, Japan, and Hong Kong in the summer of 2006 found that all 1,500 tusks had come from a concentrated area within the Selous/Niassa ecosystem. The genetic origins of these tusks all pinpointed a single area in Tanzania which suggests the work of well-placed syndicates who are able to return to the same location to hunt repeatedly with little risk. Additionally, from 2008-2013 the ivory seized in Dar es Salaam was only second to the amount seized in Mombasa, Kenya.

What makes the poaching in Selous difficult to address is quite simply the vast size of the reserve and the dense terrain that covers a large percentage of it. Both the Tanzania National Parks (TANAPA) and Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI) are responsible for animals within the national parks; however, they’ve been working with limited resources. This is why TAWIRI enlisted a partner in the Friedkin Conservation Fund (FCF) to combat the decline in the elephant population and demonstrate that Tanzania is committed to safeguarding its immense and unique wilderness heritage.

The greater Selous ecosystem requires special attention of all concerned conservation partners because it is the only area that can guarantee a sufficient space for elephants and other wildlife, but it is also of ecological importance because it is home to huge, diverse and exceptional Miombo and Savanna ecosystem. FCF feels it is not only the responsibility of Tanzania and its people to look after that important heritage but that we all should contribute to ensuring that future generations can experience and enjoy Africa’s unspoiled wilderness. FCF provides proactive assistance to the Tanzanian Government and the people of Tanzania with their efforts to conserve their network of protected areas; engages rural communities in the conservation of their natural heritage and empower them to alleviate some of the conditions that contribute to poverty; and monitors, researches and facilitates initiatives in sustainable utilization of natural resources.

On the first day, September 5, I flew the R44 from Arusha to Mikumi following the crystal-clear river.

This is why for seven days starting September 4, FCF contracted me to work alongside TAWIRI to collar 13 elephants in the greater Selous ecosystem. The elephant collars will be used for similar reasons in Selous as in the Mara: they will allow for real-time monitoring and increased security for elephants to protect them from poaching by alerting rangers and field teams about elephant location. It will also identify critical habitats, seasonal dispersal areas and corridors for elephants that may require enhanced protection. The collars overall will strengthen elephant conservation efforts in Selous Game Reserve.

Here is the entire Selous team with an elephant collar in front of the FCF R44 before our first operation.

I was excited to fly the FCF R44 and loved the all black paint job. Here’s the first day going through the helicopter.

Collaring 13 elephants in a week proved an ambitious task but along with TAWIRI veterinarians Dr. Robert Fyumagwa and Dr. Edward Kohi, I’m happy to report that all of the elephant collaring operations went successfully thanks to the use of the Robinson R44 helicopter provided by FCF, the highly mobile and dedicated team of TAWIRI vets and scientists. Collaring elephants in Selous was much more difficult than in the Mara. It’s a bigger area with much thicker brush and longer grass so the elephants are more scattered and often found in very remote locations. In the western portion of Selous lies the Miombo Forest, a vast forest filled with dense foliage where little is known about the elephant population.

This video shows the vast Miombo Forest where it’s just 100 nautical miles of this dense foliage from western Selous near Malawi and Zambia to eastern Selous near the coast.

The Miombo Forest was just an endless sea of green foliage.

TAWIRI vet Dr. Kohi and Robert collaring an elephant in the Miombo Forest.

Most days we were able to collar two to three elephants, but we got lucky on September 7 when we were able to collar four elephants in the Miombo Forest. It was really thick brush that provided little openings to land as the grass was simply too long. So, we had to land by the river bed and walk in for the collaring operation. That day we flew for 7-hours straight because of the difficult conditions for collaring but this forest was essential to understand how elephants use this ecosystem.

This was my landing spot in the Miombo Forest. There were only a few spots to land that day and near the river bed was the safest.

This proved to be a tricky landing spot in the Miombo Forest.

Our team taking a break while we refilled the helicopter on the day we flew 7 hours and collared four elephants.

In all we collared one male and 12 female elephants concentrating on candidates that represented larger herds and herds which were known for going into conflict areas. First, when we were in Mikumi, I thought this looks easy – large open spaces with very little cover; little did I know that the long grass would become a major concern because it could easily get tangled in the tail rotor of the helicopter. Additionally, the distances between collaring base stations were all over 100 nautical miles apart making logistics for fuel and repositioning of ground teams a logistical feat. Each protection station was unique and it was a good chance to see the Selous outposts and meet the rangers from an insider’s perspective. Despite the challenges presented by the terrain, I really enjoyed working with TAWIRI and flying the FCF helicopter over such beautiful landscapes.

This was an important operation for Mara Elephant Project as our work requires that we expand into a larger area of operation including the Serengeti to connect the Mara elephant movements and protection into Tanzania. In order for us to do this, TAWIRI is going to be an important part of ensuring data sharing is done across boundaries. Furthermore, sharing my expertise on elephant collaring operations is an overarching theme at Mara Elephant Project. We believe that collaboration between NGOs not just in Kenya but in Africa to protect elephants and conserve critical habitats for them and other wildlife is essential. I would like to thank the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI) and the Friedkin Conservation Fund (FCF) for their dedication to protecting wildlife in this critical ecosystem in Tanzania.

This was the first elephant collaring operation on September 5.  This was lucky number 13 on the last day of collaring, September 10.

This was lucky number 13 on the last day of collaring, September 10.