We all like a good story; one of adversities and triumphs and conservationists have some of the best stories to tell. Meet Owino Raymond, an early career conservation biologist working at Mara Elephant Project as a data and reporting manager before heading to the University of Arizona later this year to pursue his Ph.D. Raymond holds a master’s degree in biology of conservation from the University of Nairobi and has been recognized for his conservation work and leadership skills with awards for the Conservation Leadership Programme, the Society for Conservation Biology and the African Graduate Fellowship by the American Society of Mammologist. While impressive, Raymond’s journey from humble beginnings is an inspirational tale for young conservationists. Raymond didn’t choose conservation; conservation chose him as if it was fate.

We all like a good story; one of adversities and triumphs and conservationists have some of the best stories to tell. Meet Owino Raymond, an early career conservation biologist working at Mara Elephant Project as a data and reporting manager before heading to the University of Arizona later this year to pursue his Ph.D. Raymond holds a master’s degree in biology of conservation from the University of Nairobi and has been recognized for his conservation work and leadership skills with awards for the Conservation Leadership Programme, the Society for Conservation Biology and the African Graduate Fellowship by the American Society of Mammologist. While impressive, Raymond’s journey from humble beginnings is an inspirational tale for young conservationists. Raymond didn’t choose conservation; conservation chose him as if it was fate.

At a young age Raymond was orphaned and adopted by his uncle where he joined his eight cousins at their home in Siaya County in the Nyanza region in the western part of Kenya. Raymond as a child gravitated toward animals doting on his pet cats and dogs and he always enjoyed his chores herding and milking cattle the most. Raymond also loved travel and every chance he got he’d join his dad to travel throughout Kenya for his electrical engineering job. He always had an interest in biology and when he reached university Raymond was encouraged to pursue a wildlife management degree, which, at the time, he thought wasn’t going to be a good fit. “For most Africans, a career in conservation isn’t viewed as sustainable, especially if you are from a simple background,” says Raymond.

Most African universities are underfunded and lack the resources to train their students on the field applications of the theoretical knowledge learned in classes. Then, upon graduation, most African students are expected to acquire the field application experience through limited pro-bono work. Now, when you’re from a large family and have the opportunity to go to university, then graduate university, you’re expected to support your younger sibling’s financially, which deters bright young Africans from pursuing a field of work that relies on passion and not income. “The pressure to provide for your family means that a majority of underprivileged African students in conservation always end up in a different career,” says Raymond. “To put this into context, out of the 21 students I graduated with in the class of 2017, only two are still actively pursuing research and conservation.”

Despite the pressures, Raymond’s passion for conservation was lit while at university when he interned at Mara North Conservancy and got to see the impact that wildlife data collection when paired with computer-based tools can have to solving the human-wildlife conflict crisis, and it couldn’t be ignored. After university, Raymond built his field conservation experience focusing on giraffes working with the Somali Giraffe Project in northern Kenya. Through grant funding Raymond pursued, he and his team focused on solutions to mitigate human-wildlife conflict with a focus on giraffes in Garissa. They tested various technologies and techniques to prevent and mitigate conflict including using solar powered motion sensor floodlights and loud audio sounds to deter the giraffes from predating their farms. This was also Raymond’s first introduction to field work, using a motorbike to move around the rough terrain in Garissa.

Despite the pressures, Raymond’s passion for conservation was lit while at university when he interned at Mara North Conservancy and got to see the impact that wildlife data collection when paired with computer-based tools can have to solving the human-wildlife conflict crisis, and it couldn’t be ignored. After university, Raymond built his field conservation experience focusing on giraffes working with the Somali Giraffe Project in northern Kenya. Through grant funding Raymond pursued, he and his team focused on solutions to mitigate human-wildlife conflict with a focus on giraffes in Garissa. They tested various technologies and techniques to prevent and mitigate conflict including using solar powered motion sensor floodlights and loud audio sounds to deter the giraffes from predating their farms. This was also Raymond’s first introduction to field work, using a motorbike to move around the rough terrain in Garissa.

“Funding for field work and research like this is limited and when you’re an early career conservation researcher, not much faith is bestowed upon you,” says Raymond. “It was essential for me to make every connection possible and hone my written and spoken English to find opportunities in conservation. That’s what led me to Mara Elephant Project.”

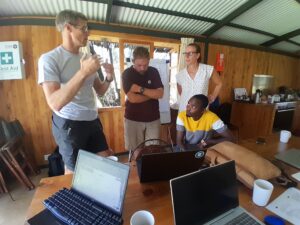

Raymond’s currently putting his talents to work at Mara Elephant Project as the data and reporting manager. Raymond helps MEP manage and report on the geospatial database using the suite of both MEP developed and partner developed conservation technologies.

Raymond’s currently putting his talents to work at Mara Elephant Project as the data and reporting manager. Raymond helps MEP manage and report on the geospatial database using the suite of both MEP developed and partner developed conservation technologies.

“I strongly feel that conservation science should not be done for the sake of science but for the purpose that leads to practical, on the ground conservation solutions and Mara Elephant Project is the epitome of science that leads to this.”

Owino Raymond

He’s also providing training to younger MEP researchers to build their skillset which allows them to advance in the field of conservation. “Mentorship in this career is essential”, says Raymond. He is here because of mentorship from well-known research scientists like Dr. Jesse Alston, a professor at the University of Arizona and MEP’s Director of Research and Conservation Dr. Jake Wall.

Like MEP, Raymond is working to create opportunities for young Kenyan conservationists interested in pursuing research. “I am a peddler of hope,” says Raymond. “Most stories in conservation are discouraging, but we also have very interesting stories that give people hope, and I think MEP is one of those stories.”