Using innovative techniques and technologies, many developed in-house, Mara Elephant Project monitors the ecosystem as a whole and the elephants and people that call it home. We collect ecological datasets like elephant movements and population, weather and climate as well as vegetation to inform our protection efforts.

MEP MONITORING TECHNIQUES AND TECHNOLOGIES

MEP is focused on increasing the amount of demographic data it is collecting on the Mara elephant population. In 2021, the MEP Research Department launched a long-term monitoring (LTM) team that is tasked with gathering individual based sightings and re-identification of elephants across the Mara, and ground-based census of elephants along fixed routes within the conservancies and protected areas. The long-term monitoring of elephant populations is used to collect important information about demographics to help our organization grow our database of known elephant individuals. Information like overall population size, age and sex structure, births, deaths, injury and disease rates help us better understand the elephant population in the Greater Mara Ecosystem (GME).

MEP is focused on increasing the amount of demographic data it is collecting on the Mara elephant population. In 2021, the MEP Research Department launched a long-term monitoring (LTM) team that is tasked with gathering individual based sightings and re-identification of elephants across the Mara, and ground-based census of elephants along fixed routes within the conservancies and protected areas. The long-term monitoring of elephant populations is used to collect important information about demographics to help our organization grow our database of known elephant individuals. Information like overall population size, age and sex structure, births, deaths, injury and disease rates help us better understand the elephant population in the Greater Mara Ecosystem (GME).

Additionally, monitoring individual elephants over time by re-sighting the same individuals is an important part of behavioral research. It can help us better understand habitat preference and identify crop-raiding elephants by monitoring injuries and look for other signs of conflict. The MEP LTM team is also gathering data that establishes the relative density and distribution of elephants in relation to season, livestock and other factors affecting the spatial distribution of elephants across the ecosystem. Although collar data provides very granular and detailed observation of a small number of individual elephants, regular elephant census will provide a more general overview of what the population is doing as a whole.

Since 2011, Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), Wildlife Research and Training Institute (WRTI) and MEP have collared over 80 flagship elephants across threatened ecosystems. A long-term collaboration between KWS, WRTI and MEP informs elephant collaring operations to understand habitat connectivity, resource allocation, conflict mitigation and elephant protection.

“We are putting collars on these elephants with KWS and WRTI so we know where the elephant is, because it’s overlaid onto Google Earth. The collars also have built-in software that if they stop we get immobility alerts.” MEP CEO Marc Goss

COLLARING

When collaring, KWS, WRTI and MEP focus on candidates that will gather useful spatial data meaning elephants in border areas, areas of conflict or areas outside conservancies or national reserves. We are also looking for candidates that represent crop raiding elephants identified across the dispersal area and candidates that represent large herds. The collared elephants in most cases represents a whole herd that may be at risk.

MONITORING

![]() KWS, WRTI and MEP monitor elephants in real-time daily. MEP’s EarthRanger tracking platform can detect when an elephant becomes immobile, breaches a geo-fence, or starts to move slowly which could indicate an injury or illness. These alerts allow MEP to react at a moment’s notice. Ground patrol ranger units are sent coordinates daily that they use to monitor the collared elephants and it’s possible to see settlements near a collared elephant, which is used to anticipate possible human-elephant conflict incidents and intervene before they occur. MEP also has an extensive geo-fence database, which acts as a warning system for collared elephants when they near settlement areas or farms.

KWS, WRTI and MEP monitor elephants in real-time daily. MEP’s EarthRanger tracking platform can detect when an elephant becomes immobile, breaches a geo-fence, or starts to move slowly which could indicate an injury or illness. These alerts allow MEP to react at a moment’s notice. Ground patrol ranger units are sent coordinates daily that they use to monitor the collared elephants and it’s possible to see settlements near a collared elephant, which is used to anticipate possible human-elephant conflict incidents and intervene before they occur. MEP also has an extensive geo-fence database, which acts as a warning system for collared elephants when they near settlement areas or farms.

All managers and officers at MEP are equipped with iPhones and the EarthRanger mobile app – a specialized and secure platform for visualizing real time elephant movement.

“We have the app on our phones. If an elephant is not moving, we get an immobility alert message, that is when we deploy our rangers.” MEP Manager Wilson Sairowua

The app also quickly highlights streaks, day and night movements and has a comprehensive base map. Managers can now easily relay coordinates to field teams and track the elephants on the ground and by air to keep them safe.

DATA COLLECTION

KWS, WRTI and MEP collared elephants provide data that is being used daily to mitigate human-elephant conflict, inform ranger deployment and anti-poaching work, and promote transboundary cooperation within the wider ecosystem. The data collected from collared elephants is used to generate monthly tracking reports and density and movement maps to better understand elephant movement patterns and behavior. The collar data is also building up a valuable database on the spatial movements and resource selection of elephants. Particularly useful are longitudinal datasets that can show changes in movements over time in response to changing environmental and anthropogenic conditions. A total of 30 elephants with active collars are needed in the GME to provide the data needed to ensure KWS, WRTI and MEP’s protection and safety of the elephants either from poaching or human-elephant conflict. This number of active collars also provides a statistically viable sample for understanding elephant range, identifying corridors and assessing the connectivity and changes in elephant movement across the landscape. This is why KWS, WRTI and MEP continue to collar.

KWS, WRTI and MEP collared elephants provide data that is being used daily to mitigate human-elephant conflict, inform ranger deployment and anti-poaching work, and promote transboundary cooperation within the wider ecosystem. The data collected from collared elephants is used to generate monthly tracking reports and density and movement maps to better understand elephant movement patterns and behavior. The collar data is also building up a valuable database on the spatial movements and resource selection of elephants. Particularly useful are longitudinal datasets that can show changes in movements over time in response to changing environmental and anthropogenic conditions. A total of 30 elephants with active collars are needed in the GME to provide the data needed to ensure KWS, WRTI and MEP’s protection and safety of the elephants either from poaching or human-elephant conflict. This number of active collars also provides a statistically viable sample for understanding elephant range, identifying corridors and assessing the connectivity and changes in elephant movement across the landscape. This is why KWS, WRTI and MEP continue to collar.

The ongoing collection of data and further analysis must continue to provide the evidence underpinning the communications and advocacy efforts of the organization to protect this critical habitat into the future.

Not only for elephants, but all wildlife that are represented by this umbrella species.

EarthRanger is a specialized conservation software that collects information in real time from all of MEP’s assets including rangers, vehicles, cameras and KWS and WRTI elephant collars that we quickly analyze and use to react.

“We’re tracking elephants, rangers, vehicles, helicopters and so on. Providing tools that can then grab the data in real time and visualize where everyone is. So, that gives us real-time insight.” MEP Director of Research and Conservation Dr. Jake Wall

Co-developed by MEP’s Director of Research and Conservation Dr. Jake Wall, Save the Elephants and Allen Institute for AI (AI2, formerly Vulcan Inc.), all of MEP’s data is stored in a secure cloud platform and readily accessible to visualize through the app, Google Earth or downloaded for further analysis within GIS software. MEP’s EarthRanger software is also being used in collaboration with other organizations that share a similar mission and by using a common platform, it promotes collaborations with other research groups to find solutions that benefit the GME.

Co-developed by MEP’s Director of Research and Conservation Dr. Jake Wall, Save the Elephants and Allen Institute for AI (AI2, formerly Vulcan Inc.), all of MEP’s data is stored in a secure cloud platform and readily accessible to visualize through the app, Google Earth or downloaded for further analysis within GIS software. MEP’s EarthRanger software is also being used in collaboration with other organizations that share a similar mission and by using a common platform, it promotes collaborations with other research groups to find solutions that benefit the GME.

“Using EarthRanger as our primary data collection and storage tool will help us toward our long-term goal of protecting elephants and their environment and will promote research, collaborations with other organizations and data-driven conservation.” Dr. Jake Wall

The MEP research department continues to improve upon MEP’s EarthRanger system. For example, Global Forest Watch (GFW) has partnered with EarthRanger to provide satellite data including GLAD deforestation alerts and VIIRs fire alerts, which are crucial to our forest monitoring efforts. These alerts detect forest loss events so that MEP can respond to them in near real-time by sending our helicopter or ranger teams to investigate. Many of these advances were made possible thanks to support from AI2, Esri, the Microsoft AI for Earth program and the Smithsonian Institute.

“The use of satellite imagery through Global Forest Watch’s GLAD Alerts has enhanced the way vast areas are monitored. This empowers conservationists to be aware of deforestation in remote places and to deal with previously impossible challenges of scale.” EarthRanger Director Jes Lefcourt

Since 2015, thanks to the generosity of the Karen Blixen Camp Trust (KBCT), Mara Elephant Project operates the only helicopter dedicated to wildlife in the Mara. Piloted by CEO Marc Goss, the helicopter monitors and protects wildlife and wild spaces in the Mara.

It’s used for …

- Aerial Reconnaissance: These aerial reconnaissance missions are used to spot illegal logging and charcoal operations or a poacher’s camp from the air then relay the coordinates to the ranger team on the ground for them to pursue.

- Monitoring of Collared Elephants: We regularly monitor KWS and MEP’s collared elephants by air to check on their well-being and the overall health of their herd. Through the aerial monitoring program, we have identified the collared elephants represent between 400 and 600 elephants.

- Conflict Mitigation: The helicopter works extremely well to mitigate conflict when used alongside our rangers on the ground, who are our first line of defense. It also has the advantage of increasing the rapid response time to conflict, when the terrain is difficult, and expanding our operational area thanks to the helicopter’s ability to traverse a large area in a short period of time.

- Building Partnerships: Since MEP has the only operating helicopter dedicated to wildlife in the Mara, it is essential not only for us, but for our partners, like Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS). A KWS Vet with the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust (SWT) Mobile Vet Unit performs the elephant treatments in the Mara and MEP provides both aerial and ground support to the team ensuring the elephant treatment is safe for personnel and the animal being treated. Additionally, locating an injured elephant from the air improves response time to treat the injured elephant and can often spot an injury in otherwise impossible circumstances like thick vegetation. The helicopter is also effective at dropping seed balls from Seedballs Kenya, our partners who join us to cover a large area in need of reforestation.

- Other Wildlife: MEP’s helicopter is also used to assist other wildlife living in the Mara. The helicopter has been used to gather information on the critically endangered mountain bongo antelope living in the Mau Forest, it’s been used to assist with treatments of lions, giraffes, buffalo and rhino as well as to investigate the cause of death of various other wildlife and to complete well-being checks on the endangered black rhino. It’s had baby elephant passengers on their way to the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust orphanage and a vulture on the way for treatment after a poisoning incident.

- Collaring Operations: The MEP helicopter is an essential element to the KWS and MEP elephant collaring operations ensuring both our personnel and the elephant are safe while deploying the collar.

-

Saving Lives: The helicopter has been used for EMS flights for community members, conservancy rangers and MEP staff. All ensuring they make it to treatment in time when their location is remote.

The helicopter is a vital part of our operations to protect elephants, other wildlife and local communities across the Mara ecosystem.

Mara Elephant Project has developed bespoke conservation technology in house to solve some of the time consuming and costly challenges facing organization making data-based conservation decisions. ElephantBook is a custom software developed by MEP in collaboration with partners that automates the identification of elephants using information captured by MEP’s LTM team.

Monitoring elephant population dynamics is essential in conservation efforts and although there have been many recent successes in the use of computer vision techniques for automated identification of other species, identification of elephants is extremely difficult and typically requires expertise as well as familiarity with elephants in the population.

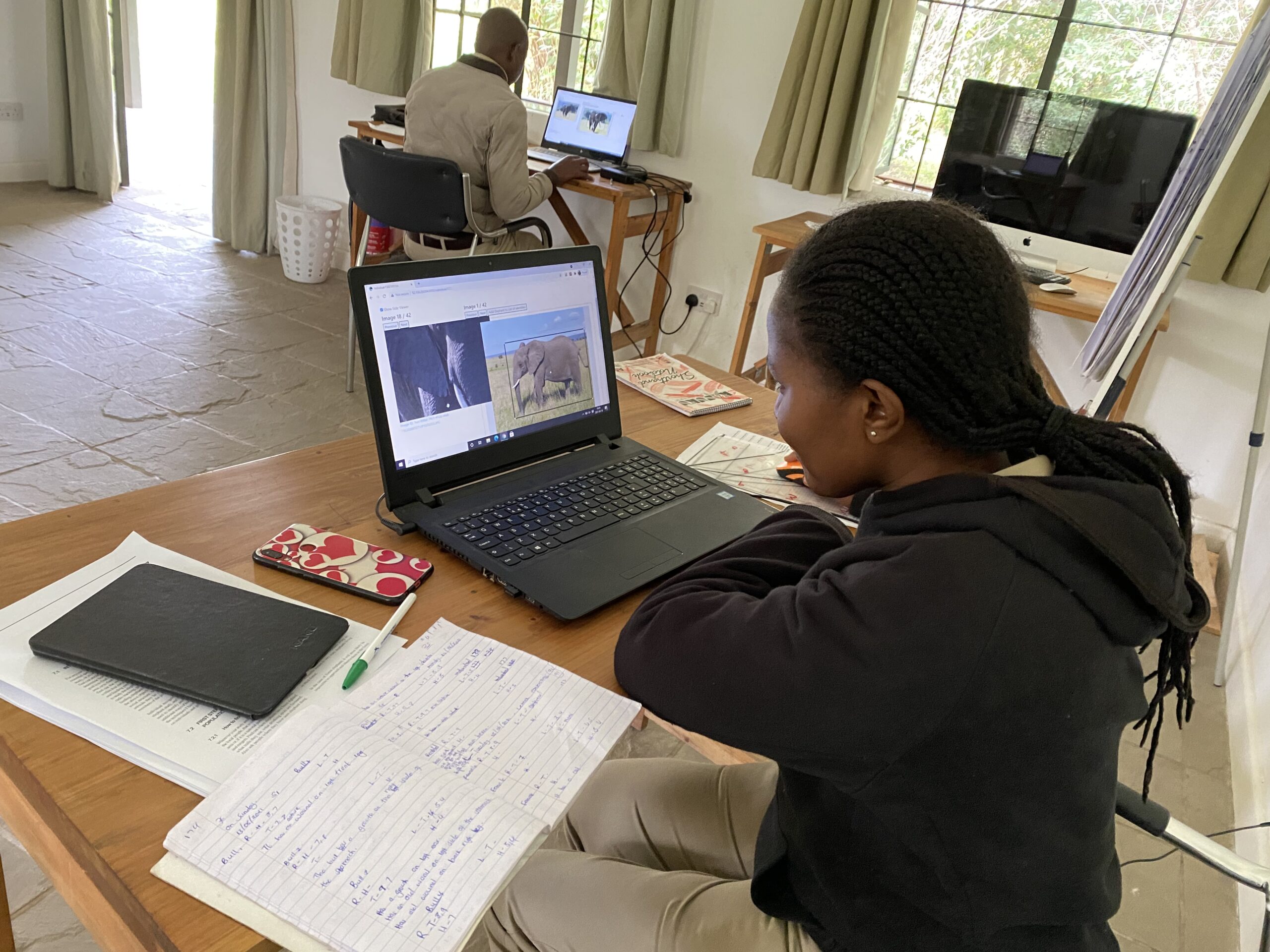

That is why MEP and partners developed and deployed a web-based platform and database for human-in-the-loop re-identification of elephants combining manual attribute labeling done by the MEP LTM team and state-of-the-art computer vision algorithms, known as ElephantBook. Ecologists have recently attempted to create a general re-identification method that can be used by non-experts. The best known of these methods is System for Elephant Ear-Pattern Knowledge (SEEK) coding, developed by Elephants Alive, which uses manual attribute labels such as sex and the presence/absence of tusks to improve the accuracy and efficiency of re-identification. MEP in collaboration with the California Institute of Technology and Elephants Alive developed a semi-automated ensemble visual-recognition system using photographs taken by the LTM team along with manual SEEK attribute labeling. You can read more about ElephantBook in the manuscript co-authored by MEP, “ElephantBook: A Semi-Automated Human-in-the-Loop System for Elephant Re-Identification”.

Here’s the process. The MEP LTM heads into the field for the day to gather extensive information on an individual elephant so that the same elephant and family herd can be identified correctly again to be monitored over time. They take high resolution images of all sexually mature elephants. Once back at headquarters, the photos are uploaded into ElephantBook to be catalogued. They start with the ears and take one ear at a time dividing it up into sections, like a clock, and noting any distinct characteristics and where they are located. For example, an elephant might have a tear at 7 or a discoloration at 4. They also note the tusks and any defining characteristics. While tusks seem to be a defining characteristic of an elephant, they can’t be solely relied upon because elephants can break their tusks. The detailed photographs are also used to note injuries that have healed or any other defining features that an elephant might have. For example, individual 2 “Flopsy”, an elephant identified by the team, is missing a tail and has a left ear that is unable to move and flops to his side.

Here’s the process. The MEP LTM heads into the field for the day to gather extensive information on an individual elephant so that the same elephant and family herd can be identified correctly again to be monitored over time. They take high resolution images of all sexually mature elephants. Once back at headquarters, the photos are uploaded into ElephantBook to be catalogued. They start with the ears and take one ear at a time dividing it up into sections, like a clock, and noting any distinct characteristics and where they are located. For example, an elephant might have a tear at 7 or a discoloration at 4. They also note the tusks and any defining characteristics. While tusks seem to be a defining characteristic of an elephant, they can’t be solely relied upon because elephants can break their tusks. The detailed photographs are also used to note injuries that have healed or any other defining features that an elephant might have. For example, individual 2 “Flopsy”, an elephant identified by the team, is missing a tail and has a left ear that is unable to move and flops to his side.

Once an elephant has been identified and catalogued in ElephantBook, the LTM team can then go out again and when they are able to successfully ID the same elephant twice, that elephant is given an official ID number, sometimes a name and adds to our growing catalogue of individuals identified. Identifying elephants previously was a more informal process and ElephantBook now allows a more approximate way to monitor the elephant population.

There are now 1,116 identified elephant individuals in ElephantBook of the 2,600 elephants that call the Mara home. Using ElephantBook MEP strives to create a unique identification number for reach resident elephant in the Mara, which will enable us to track elephant demography to approximate elephant density and abundance and estimate their survival rates. The work that the LTM team is undertaking in identifying all of the elephants in the GME is extremely important to MEP’s mission. Their work over time can help alert MEP to a resurgence in poaching in the ecosystem, it can also allow us to monitor the elephant population for any injuries related to conflict. We are also able to determine the elephant population in the GME and the makeup of the population in terms of sex, age and other characteristics. We will also be able to take monitoring information collected and apply that to ranger deployments.

There are now 1,116 identified elephant individuals in ElephantBook of the 2,600 elephants that call the Mara home. Using ElephantBook MEP strives to create a unique identification number for reach resident elephant in the Mara, which will enable us to track elephant demography to approximate elephant density and abundance and estimate their survival rates. The work that the LTM team is undertaking in identifying all of the elephants in the GME is extremely important to MEP’s mission. Their work over time can help alert MEP to a resurgence in poaching in the ecosystem, it can also allow us to monitor the elephant population for any injuries related to conflict. We are also able to determine the elephant population in the GME and the makeup of the population in terms of sex, age and other characteristics. We will also be able to take monitoring information collected and apply that to ranger deployments.

ElephantBook is a novel online software solution with the goal of making elephant re-identification usable by non-experts and scalable for use by multiple conservation NGOs. Thank you to Peter Kulits, Anka Bedetti, Michelle Henley and Sara Beery for their contributions to ElephantBook. MEP is grateful to our research partners Kenya Wildlife Service, Wildlife Research and Training Institute, Narok Country Government and Maasai Mara Wildlife Conservancies Association for supporting this effort.

Mara Elephant Project focuses on protecting elephants and their habitats across the GME and in the GME, resources for both large mammals, like elephants, and pastoralists are highly variable in space and time and thus require connected landscapes. Currently, the GME is a landscape experiencing an expansion of fences, farms and community developments which are fragmenting the landscape and cutting off important habitats for wildlife that contain essential resources. To understand how fragmentation of the ecosystem affects people and wildlife, scientists need to map human features like livestock enclosures, fences and farms, and catalogue them over time, which is what MEP is currently doing.

Mara Elephant Project focuses on protecting elephants and their habitats across the GME and in the GME, resources for both large mammals, like elephants, and pastoralists are highly variable in space and time and thus require connected landscapes. Currently, the GME is a landscape experiencing an expansion of fences, farms and community developments which are fragmenting the landscape and cutting off important habitats for wildlife that contain essential resources. To understand how fragmentation of the ecosystem affects people and wildlife, scientists need to map human features like livestock enclosures, fences and farms, and catalogue them over time, which is what MEP is currently doing.

We start with field researchers who are collecting the data on motorbikes and using an application developed by MEP called TerraChart, which is essentially a fancy GPS. The app allows the researcher to map roads, fences, infrastructure while also viewing a current map so that their efforts aren’t duplicated. The data collected through TerraChart and field forms is then cleaned and organized before it is put into the Landscape Dynamics (landDX) database, which provides a central and open-source repository for these data that is continually updated as more data is collected. The Landscape Dynamics database covers ~30,000 km2 of southern Kenya and the data includes 31,000 livestock enclosures, nearly 40,000 kilometers of fencing, and 1,500 km2 of agricultural land. Other conservation organizations contribute data to build the landDX database, which is a good example of how collaborations and data sharing between organizations can provide tools that will help improve research and conservation of wildlife and wild spaces.

This data is then used to create a basemap that provides the base for MEP’s EarthRanger system so that all of our asset movements are shown over the basemap created of the ecosystem. Then, when paired with animal location data, MEP can study how elephants and other species are responding to landscape changes. When looking at elephant movements that are then visualized over the basemap, which includes the fences, you can then start to understand why elephants move the way they do as it relates to the changes in the ecosystem. The data collected in landDX and the resulting basemaps created for the GME are shared with partners to help inform their protection efforts and to help answer fundamental ecological questions we’re all working together to solve.

The landDX database is featured in a paper co-authored by MEP, “Landscape Dynamics (landDX) an open-access spatial-temporal database for the Kenya-Tanzania borderlands” published in Nature Scientific Data in 2022. The data featured in this paper was collected from a variety of partners and sources across the region including South Rift Association of Land Owners, Aarhus University, Kenya Wildlife Trust and MEP. MEP is grateful to our research partners Kenya Wildlife Service, Wildlife Research and Training Institute, Narok Country Government and Maasai Mara Wildlife Conservancies Association for supporting this effort.

Some photographs provided by Chags Photography.